Summer of Sleaze is 2014’s turbo-charged trash safari where Will Errickson of Too Much Horror Fiction and Grady Hendrix of The Great Stephen King Reread plunge into the bowels of vintage paperback horror fiction, unearthing treasures and trauma in equal measure.

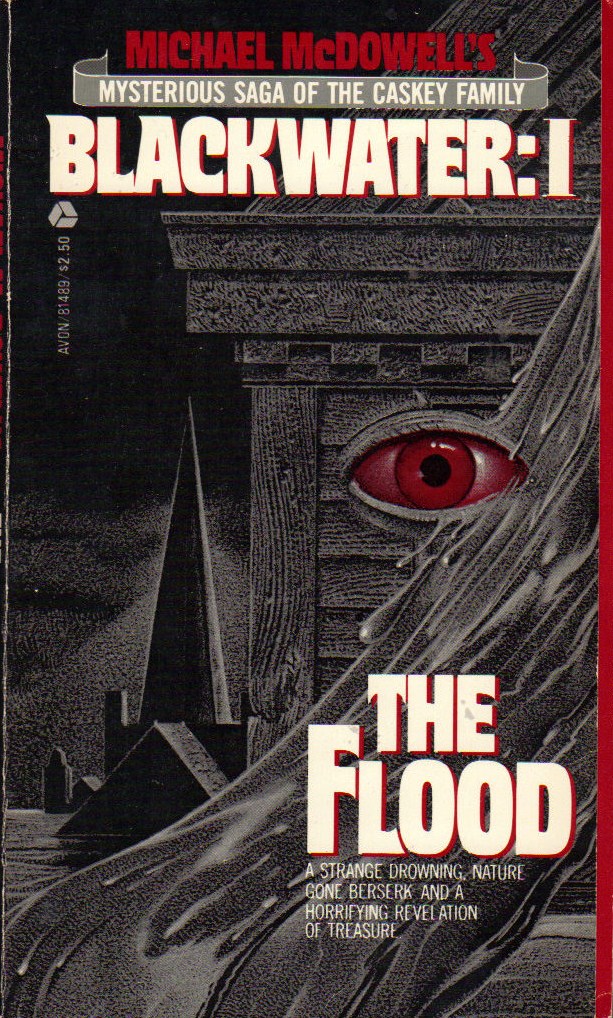

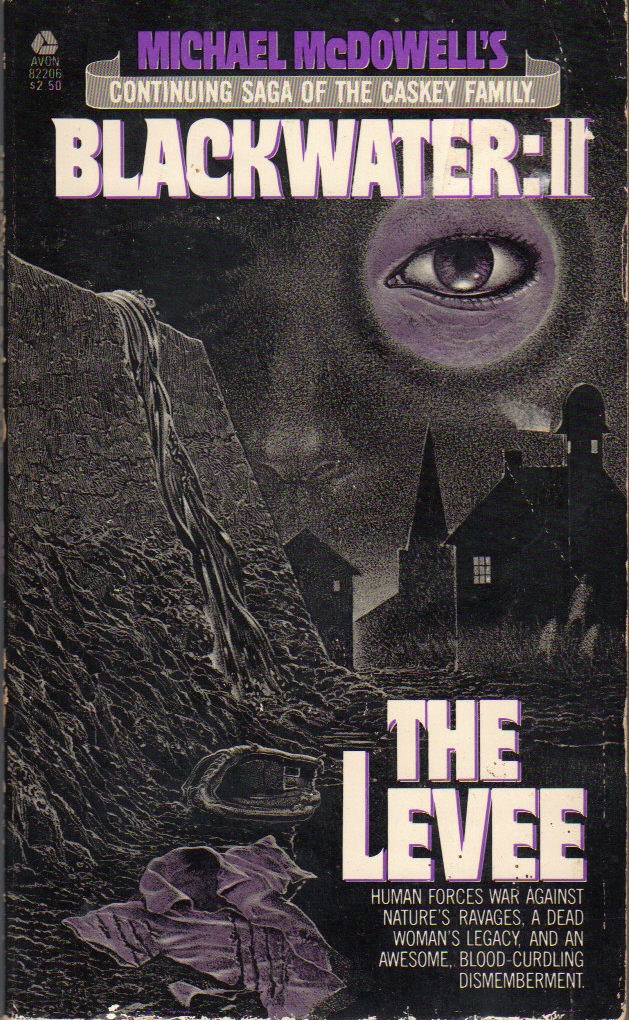

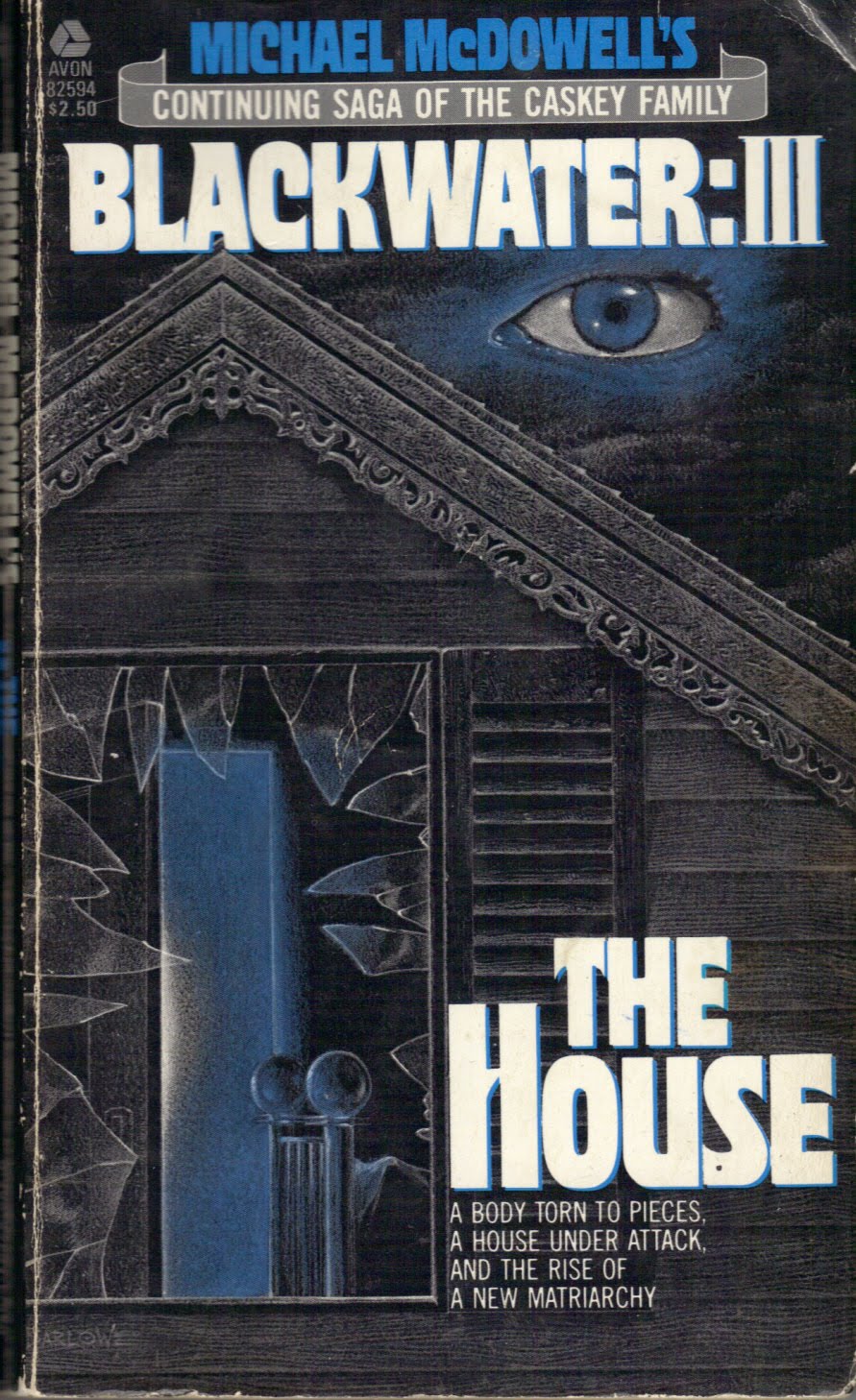

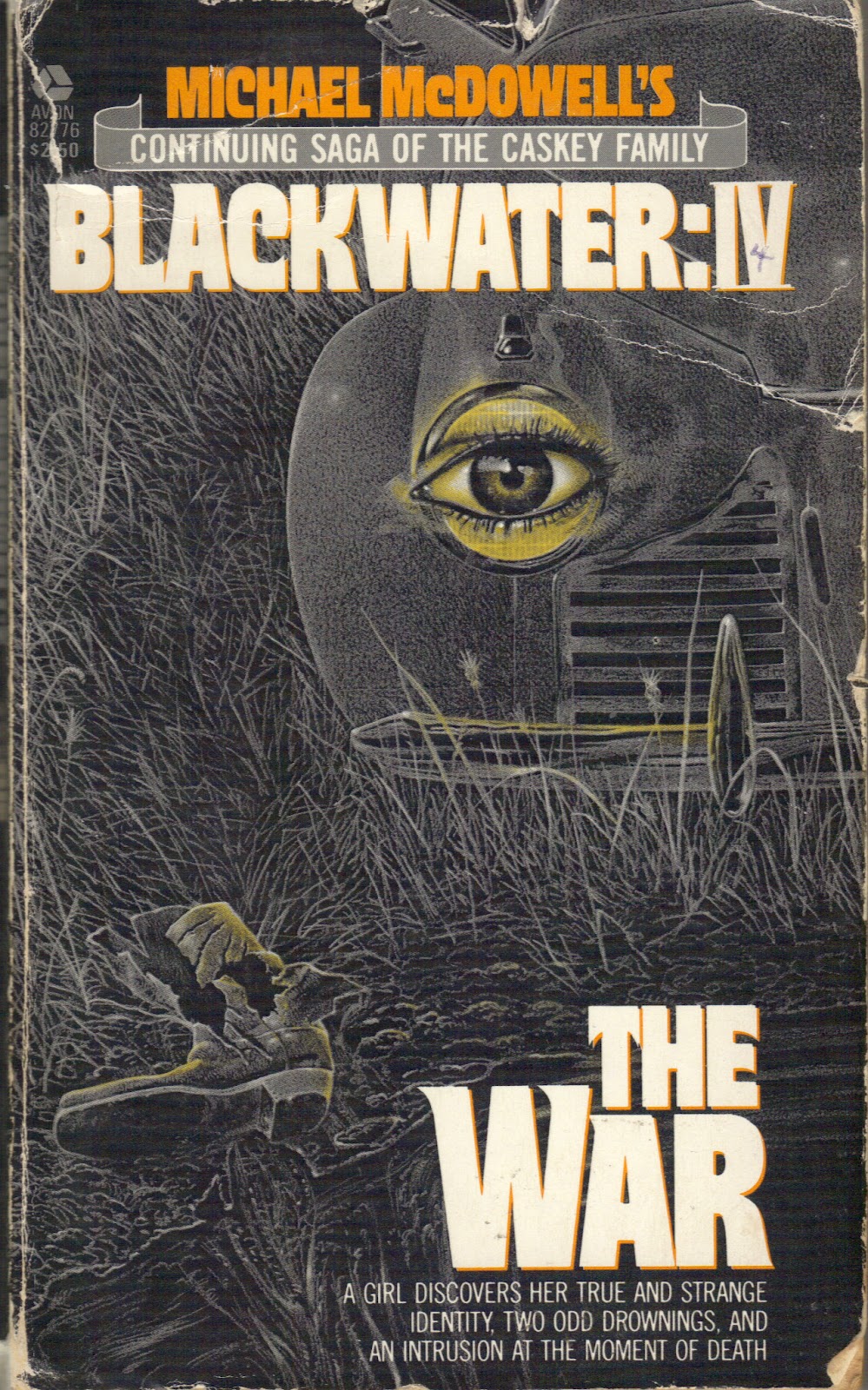

The idea of a paperback original series in the horror genre was a unique one when the six-volume Blackwater began publication by Avon Books in January 1983. Written by the prolific Michael McDowell (1950-1999), it was a many-generational story set in Alabama, a Southern Gothic-lite, mixing soap opera and horror tropes with equal ease, to be published one a month for six months.

Multi-novel series were seen most often in the science fiction and fantasy genres, or in the mystery field with countless detectives on endless cases. There had been a few pulp-horror series in the early 1970s, such as Robert Lory’s Dracula Horror Series, or the Frankenstein Horror Series by various authors, but Blackwater was decidedly unlike those. More than a full decade later, Stephen King would publish a story in the same manner—The Green Mile (and after that, of course, came John Saul’s Blackstone Chronicles. I’ve not read either but King name-checks McDowell as his inspiration in Green Mile’s preface)—and find enormous success with it.

Today of course readers could not escape multi-volume genre series even if they wanted to, but in the early 1980s, only McDowell would dare writing one. Avon Books must have had plenty of confidence in him, although in truth this series would be McDowell’s last paperback horror publication. I don’t know how successful Blackwater was, but I saw lots of creased, worn-out copies in my days as a clerk in a used bookstore more than 20 years ago, and the many Amazon and Goodreads reviews are positive. It’s even available for Kindle, and I believe Centipede Press is preparing a large, multi-volume, illustrated hardcover for a 2015 release. These moody paperback covers were done by the great science fiction and fantasy artist Wayne D. Barlowe (the illustrations come to make perfect sense as you read each book).

Together, the six volumes total nearly 1,200 pages and span half a century, so let me give a general sense of the saga, as like many a soap opera, the tangled storyline and character relationships are difficult to relate in a linear fashion. Elinor Dammert, a mysterious young woman rescued from the flood waters that overwhelmed the tiny Alabama town of Perdido on Easter Sunday, 1919, marries into the wealthy Caskey family. The Caskeys own successful sawmills on the Blackwater River, and live in a row of homes along the intersecting Perdido River, ruled over by widowed matriarch Mary-Love Caskey. Imperious, petty, and manipulative, Mary-Love distrusts Elinor from the start and watches with dismay as Elinor charms James (Mary-Love’s brother-in-law) and eventually marries Oscar (Mary Love’s son). “I knew she would do it,” Mary-Love says, “worm her way in. Dig right down in the mud of Perdido until she couldn’t be dragged out by seventeen men pulling on a rope that was tied around her neck—and I just wish it were!”

Perdido has an unspoken web of relationships and hierarchies run by old and middle-aged women; Elinor’s emergence upsets this delicate balance. The machinations and manipulations of the Caskeys are fascinating as McDowell develops them economically, without getting bogged down in psych 101 or a backstory of neuroses. An early passage reveals the very heartbeat of the entire series:

Perdido has an unspoken web of relationships and hierarchies run by old and middle-aged women; Elinor’s emergence upsets this delicate balance. The machinations and manipulations of the Caskeys are fascinating as McDowell develops them economically, without getting bogged down in psych 101 or a backstory of neuroses. An early passage reveals the very heartbeat of the entire series:

“Oscar knew that Elinor was very much like his mother: strong-willed and dominant, wielding power in a fashion he could never hope to emulate. That was the great misconception about men… there were blinds to disguise the fact of men’s real powerlessness in life. Men controlled the legislatures, but when it came down to it, they didn’t control themselves… Oscar knew that Mary-Love and Elinor could think and scheme rings around him. They got what they wanted. In fact, every female on the census rolls of Perdido, Alabama got what she wanted. Of course no man admitted this; in fact, didn’t even know it. But Oscar did…”

McDowell well understands Southern life: how the land and the rain and the flood stain lives, how familial ties can strangle and choke, how the black families still serve the white but maintain a newfound dignity, and how matriarchal power predominates, as seen in his other novels like The Amulet (1979) and The Elementals (1981). Telling much of his story at a grand remove, McDowell regales us in his unhurried prose with the history of the town, of the Caskey family and the sawmill, the lives of various non-family members, of the lengths to which some people will go to manipulate others in order to gain or regain power and respect and authority, the amassing of wealth and prestige so important to small, close-knit towns.

A Southerner himself, McDowell easily inhabits his characters from that particular region, their interior lives and thoughts and hopes and fears. The crisscrossing currents of emotional manipulation between Mary-Love and her daughter-in-law Elinor as the latter subtly begins her ascent to the Caskey throne forms the central conflict in the first half of the series. The two powerful, steel-willed women at war use any weapon at their disposal—particularly children. The second half of the series concerns Elinor’s abdication of power to her eldest daughter.

Our cast of characters is large, but it’s one that’s drawn well and believably, with all those tiny details that feel true. Sister is a Mary-Love’s spinster daughter who still lives at home; James Caskey, the brother of Mary-Love’s dead husband, is in an unhappy marriage with Genevieve and has “despite the possession of a wife and daughter… the stamp of femininity.” There are the black servants, Ivey Sapp and her daughter Zaddie, as well as Bray Sugarwhite. As the saga continues we will meet Queenie, Genevieve’s put-upon sister running from her abusive husband Carl; Billy Bronze, a handsome and intelligent North Carolina corporal; Early Haskew, an engineer hired to build a levee for the rivers; and the many Caskey children who reach adulthood: Elinor and Oscar’s daughters Miriam and Frances, James and Genevieve’s daughter Grace, Francis and Billy’s daughter Lilah, and Queenie and Carl’s children Malcolm, Lucille, and Danjo. Eventually those kids will have children too; Frances’s daughter Nerita will share Elinor’s unique heritage.

Unassumingly soap operatic in its human conflicts, McDowell tells a leisurely tale, one that eddies and flows like a lazy river. Years pass over pages, his style conveying width not depth, a tableaux of history. At times the story seems going nowhere in particular, and then suddenly McDowell will zoom in on a moment, a confrontation, a revelation, and dramatic waters roil and churn and we see how good he is at interpersonal relationships, drawing out the peculiarities of his characters and their insecurities, and he’s best at evoking darkness and dread. It’s this darkness and dread that powers Blackwater, even when lying dormant. McDowell’s real skill is sneaking up on you on that lazy river and clobbering you over the head with short, sharp shocks of violence.

McDowell stacks mystery upon mystery in a precisely calculated manner that keeps the reader turning pages, without straining credibility. Chapters end on some oblique note of unease or flat statement of uncomfortable fact, whether it be death, dismemberment, or a stand of water oak trees planted by Elinor that seem to grow overnight.

The horrors can be understated and they can also be graphic: a preacher discovers Elinor naked submerged in the muddy red waters of the Perdido, undergoing some transformation. James’s wife Genevieve is killed in a car accident, a brutal death that McDowell tinges with the blackest of humor. A man who attacks teenage Lucille at a dance is dealt with mercilessly. A young boy is swept up into the powerful junction between the Blackwater and Perdido and drowns, perhaps by something that lives at the bottom of the whirlpool, where “it grabbed you so tight your arms got broken and then it licked the eyeballs right out of your head.” Voices of dead wives and children come from the next room. And one character suffers a bone-cracking death the likes of which I haven’t read outside of a Clive Barker story; it is truly the most discomfiting scene in the whole series, one of the worst deaths I’ve read in horror; a terrific bit of 1980s paperback Grand Guignol (it happens in volume three, The House, my favorite of the series).

The central mystery is, of course, Elinor. In a way, there’s no mystery about her: it’s clear she’s not quite human, or human and something more, within the first half of volume one, The Flood. In another way, there’s lots of mystery because McDowell is a writer who underplays supernatural occurrences, letting them happen organically, flowing as they do from the natural lives of the characters. It’s a nice trick for those who appreciate quieter, more ambiguous horror fiction, to readers who like to do their own imaginative heavy lifting. This nature has been passed on to daughter Frances—witness Frances’s strange supernatural revenge upon a rapist in volume four, The War. McDowell keeps Elinor’s origins murky even when he tells us precisely what they are. The mythic kinship between mother and daughter, and to the Perdido River, speaks of Jungian shapeshifters, of ancient legends about the dark powers of women and water, their unending appetite, and the children they bear. Frances bears not only Lilah on a stormy night in volume five, The Fortune; there is another child too, one that Zaddie Sapp catches the merest glimpse of when assisting in the childbirth:

The central mystery is, of course, Elinor. In a way, there’s no mystery about her: it’s clear she’s not quite human, or human and something more, within the first half of volume one, The Flood. In another way, there’s lots of mystery because McDowell is a writer who underplays supernatural occurrences, letting them happen organically, flowing as they do from the natural lives of the characters. It’s a nice trick for those who appreciate quieter, more ambiguous horror fiction, to readers who like to do their own imaginative heavy lifting. This nature has been passed on to daughter Frances—witness Frances’s strange supernatural revenge upon a rapist in volume four, The War. McDowell keeps Elinor’s origins murky even when he tells us precisely what they are. The mythic kinship between mother and daughter, and to the Perdido River, speaks of Jungian shapeshifters, of ancient legends about the dark powers of women and water, their unending appetite, and the children they bear. Frances bears not only Lilah on a stormy night in volume five, The Fortune; there is another child too, one that Zaddie Sapp catches the merest glimpse of when assisting in the childbirth:

“Zaddie turned to turn out the light, but as she was turning she glimpsed a second head emerging smoothly from Frances’s quietly heaving body. It was greenish-gray, and it seemed to wobble. Zaddie saw two wide-open, perfectly round filmy eyes, and two round black holes where a nose ought to have been…”

Wisely, Blackwater ends as it began, with rivers overflowing to wash away the old and perhaps begin everything anew. Michael McDowell has written a rich, layered historical novel with many Southern Gothic touches, filled out with memorable characters and satisfying moments of death and shock. Its similarities with other ’80s horror fiction are found only in McDowell’s other works. Get yourself a huge glass of sweet tea, camp out beneath the summer sun, and revel in the leisured, stately, creepy story of a wealthy Southern family living at the intersection of two powerful rivers, “where all civilization seemed separated from this strange spot by space and time,” and the woman whose inhuman strength and power gives them all they desire, all they dread, and all they dream—whether they want those things or not.

Will Errickson covers horror from the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s on his blog Too Much Horror Fiction.